Dreams for a Better Tomorrow

Scientists today cracked the genome of the computer virus programmer.

(character count: 99, including title)

Dreams for a Better Tomorrow Scientists today cracked the genome of the computer virus programmer.

0 Comments

(Character count: 138, with title)

Fingers Tap. Drum. Rub together. Entwine. Clench. Bite. Chew. Wipe sweat off. Inside pockets. Sit on. Tap. Drum. His meeting starts soon. (character count: 105, including title)

Empty doesn’t live here anymore. It’s been gone for quite some time.  I'm not a theater-goer. Going to a play is not necessarily on the top of my list for a night out. Yet I sometimes enjoy reading plays. I realize this is like reading sheet-music and lyrics without hearing the music performed: the performance and the emotions of the performer gives meanings to the notes, to the words: the reader/listener is not experiencing the piece as it's meant to be experienced. But, then again, perhaps reading a play without knowledge of the performance, without the stigma of comparison. Just as when reading the book before the movie, we are the directors of what we read.

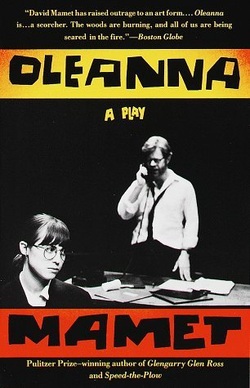

So I read Mamet's Oleanna yesterday. And, despite my preference for having an unfettered imagination when I read, without having a preconceived notion of how the characters are supposed to sound or look like, I could not help but be influenced by the cover of this edition: William H. Macy and Rebecca Pidgeon (Mamet's real-life wife). However, in this instance it did not bother me; in fact, I felt the preconceived image of these two unsympathetic characters contributed to my enjoyment. Pidgeon naturally has a stilted way of speaking, as if she's popping the bubbles of the words that have just formed, chopping them in half with her mouth, that I could hear in Carol, an at first seemingly hapless, confused student. Pidgeon's is a voice that yields itself well to self-righteous indignation and victory, which also follows the arc of her character. Macy's professor is a pedantic, harried, stammering man, the type who hides behind books when faced with a threat to his conviction of ideas, an intellectual capitulator who runs from his own ideas, only comfortable in the shadow of his self-directed disappointment. Macy could play this insecure cauldron of a person in his sleep. These two voice types fit perfectly Mamet's equally overstepping and elliptical dialogue. There are many long pauses and an artistry to the employment of the ellipse. There are very few completed sentences or ideas by either character, which is one of the points of the play: neither character is fully listening to the other one, allowing each person's words and intentions to be fully misinterpreted and later easily exploited. As I said, neither character is sympathetic. The play is a very simple concept and idea executed to an expert level: an exploration of how seemingly innocuous statements can be used as attacks, of how words can be manipulated to fulfill one's purpose; an exploration of power, as explored through the manipulation of language, and sometimes poorly judged actions. There is almost no better exploration in scene of the shifting of power between two characters in all of literature, except perhaps the book scene in Ishiguro's Remains of the Day, or Richard Bausch's "Someone to Watch Over Me." (Disclaimer: I am being deliberately vague in my not using any examples. To give examples would be to wrongfully mislead you into thinking a certain thing about either character, especially when so much hinges on the reader's interpretation of ambiguity.) All of this leads to the ultimate display of power, or the only means by which a character/person who has been made to feel powerless can yield power again. A shocking ending, not in its occurrence as the dynamics of the characters builds to it, but in its ferocity. And a final line that places the entire motives of both characters into question. As stated above, I do not regularly attend the theater, but I would make an exception for this. (character count: 66)

Monologue He suddenly realized he was running out of things to say. |